iTOP

Mastering Mechanical Biofilm Control with Individually Trained Oral Prophylaxis (iTOP)

Interdental spaces

Interdental spaces are the gaps between adjacent teeth that play a critical role in maintaining oral health. These spaces can change throughout life depending on factors like the transition from primary to secondary dentition, the presence of periodontal diseases, or undergoing orthodontic, periodontal, implant, or prosthodontic treatments. Understanding the anatomy of interdental spaces is essential because these spaces are dynamic and vary from patient to patient and from site to site. Regular assessment of interdental spaces is crucial for choosing the right tools and techniques for effective interdental cleaning.

Additionally, it is important to factor in the patient’s dexterity, motivation and preferences and cost and availability of products when selecting mechanical plaque control devices to ensure a tailored approach that supports their oral health. Research supports that managing these spaces properly is key to preventing food impaction, reducing plaque accumulation, and mitigating the risk of periodontal diseases.

ID spaces in health and in disease

In healthy dentition, where teeth are in contact, the interdental (ID) space is mostly triangular. The sides of this triangle are formed by the surfaces of adjacent teeth or their restorations, while the base is the tip or base of the interdental papilla, depending on its on position. The central area of the papilla, known as the col, is a non-keratinized portion of the interdental gingiva located beneath the contact point. Due to its delicate nature, the col is more prone to inflammation and disease. The apex of the triangular space corresponds to the apical portion of the contact point, represented by the surfaces of the crowns of the adjacent teeth.

Why is it important to maintain interdental space biofilm free?

Interdental (ID) spaces account for approximately 40% of all tooth surfaces that require de-plaqueing to prevent the common oral diseases, such as dental caries and biofilm induced gingivitis and periodontitis.

Interdental spaces

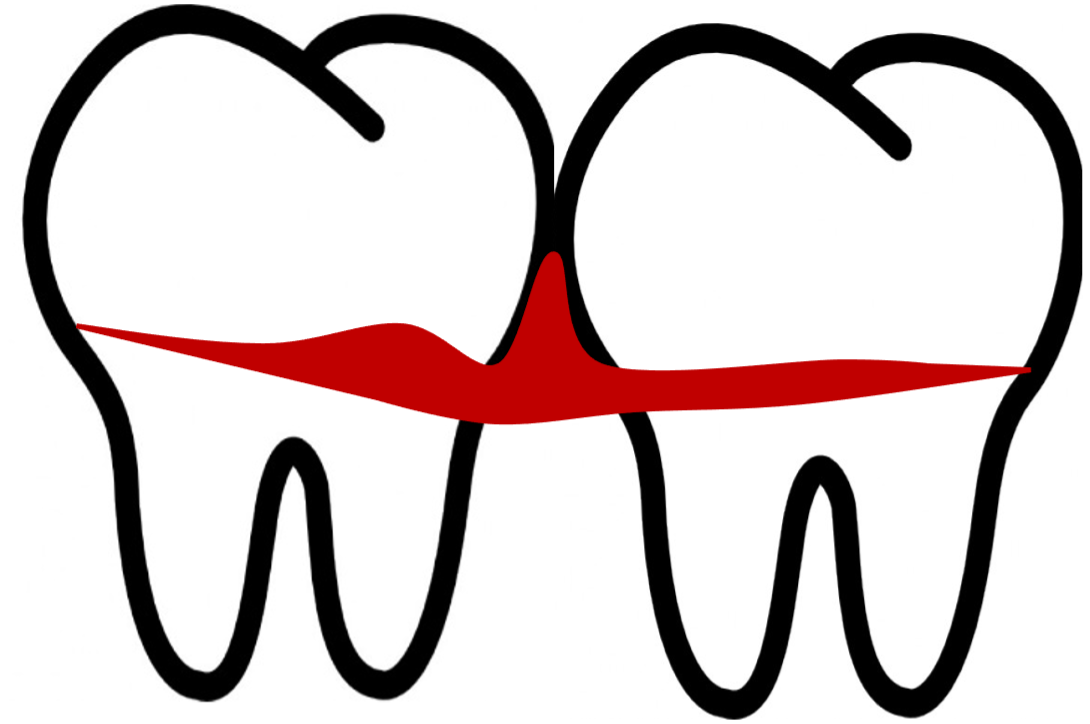

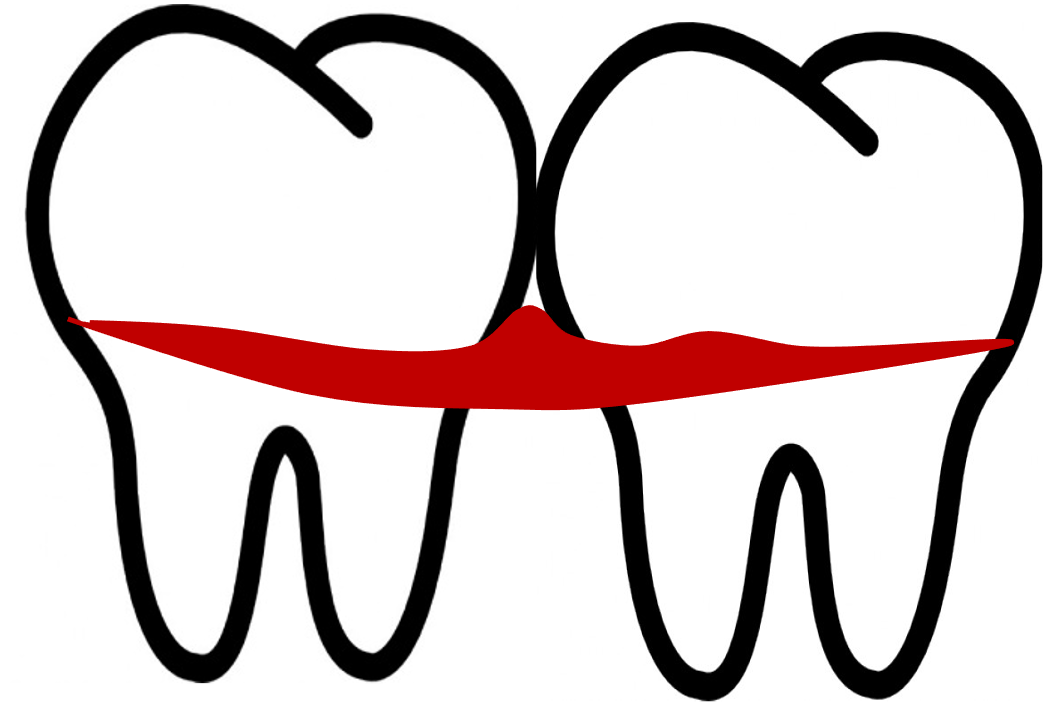

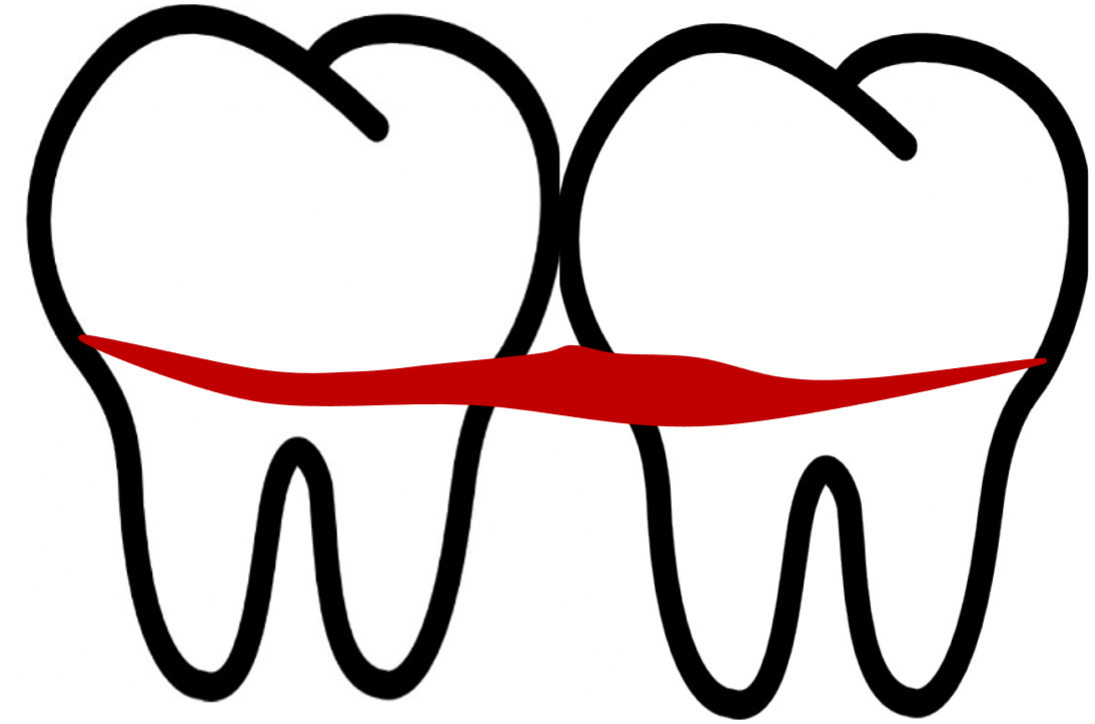

In a healthy periodontium, the interdental space is typically filled with interdental gingiva (papilla), creating a gingival embrasure classified as type I. However, when the interdental papilla recedes slightly, leaving a small gap between the teeth, it is referred to as gingival embrasure type II. In cases of advanced periodontitis, severe gum disease, or significant orthodontic misalignment, the papilla may recede entirely, exposing the entire proximal surface of the tooth, and sometimes even the root surface. This condition is classified as gingival embrasure type III. Understanding these classifications is essential for effective planning of interdental biofilm control recommendations.

Gingival embrasure type:

Gingival embrasure type I

Gingival embrasure type II

Gingival embrasure type III

Two devices commonly used for mechanical plaque control in interdental spaces are dental floss and interdental brushes both of which are effective for maintaining oral hygiene when selected and used correctly.

Dental floss, as we know it, was invented in 1815 by a dentist from New Orleans. He recommended using a thin silk thread to clean between teeth, marking the first recorded use of floss for interdental cleaning. Today, nylon, PTFE and polyester have replaced silk, as more durable synthetic materials.

Dental floss, while widely recognised, is often underutilised due to its perceived difficulty of use and its relative ineffectiveness in removing biofilm compared to interdental brushes. This has been supported by research, including a meta-analysis published in 2015 in the Journal of Clinical Periodontology, which concluded that flossing is not the most effective method for interdental cleaning. The analysis highlighted that interdental brushes outperform floss in terms of biofilm removal and user compliance, making them the preferred choice for most individuals, especially in spaces large enough to accommodate their use.

Analysing the anatomy of interdental spaces reveals that interdental brushes, when properly sized, can remove more biofilm than dental floss. This is particularly critical for posterior teeth, such as premolars and molars, which often feature mesial and distal concavities. These anatomical variations make thorough cleaning with dental floss challenging, whereas the bristles of interdental brushes can adapt to these contours, enhancing biofilm disruption and removal.

A meta-analysis evaluated patient preferences between interdental brushes and dental floss, revealing a clear preference for interdental brushes. Despite their potential to bend, buckle, or distort during use, patients found interdental brushes simpler and more convenient, making them the favoured choice for interdental cleaning. These findings highlight the importance of selecting tools that align with both patient preferences and ease of use for optimal oral hygiene practices.

What factors should guide the choice between dental floss and interdental brushes for effective mechanical biofilm control?

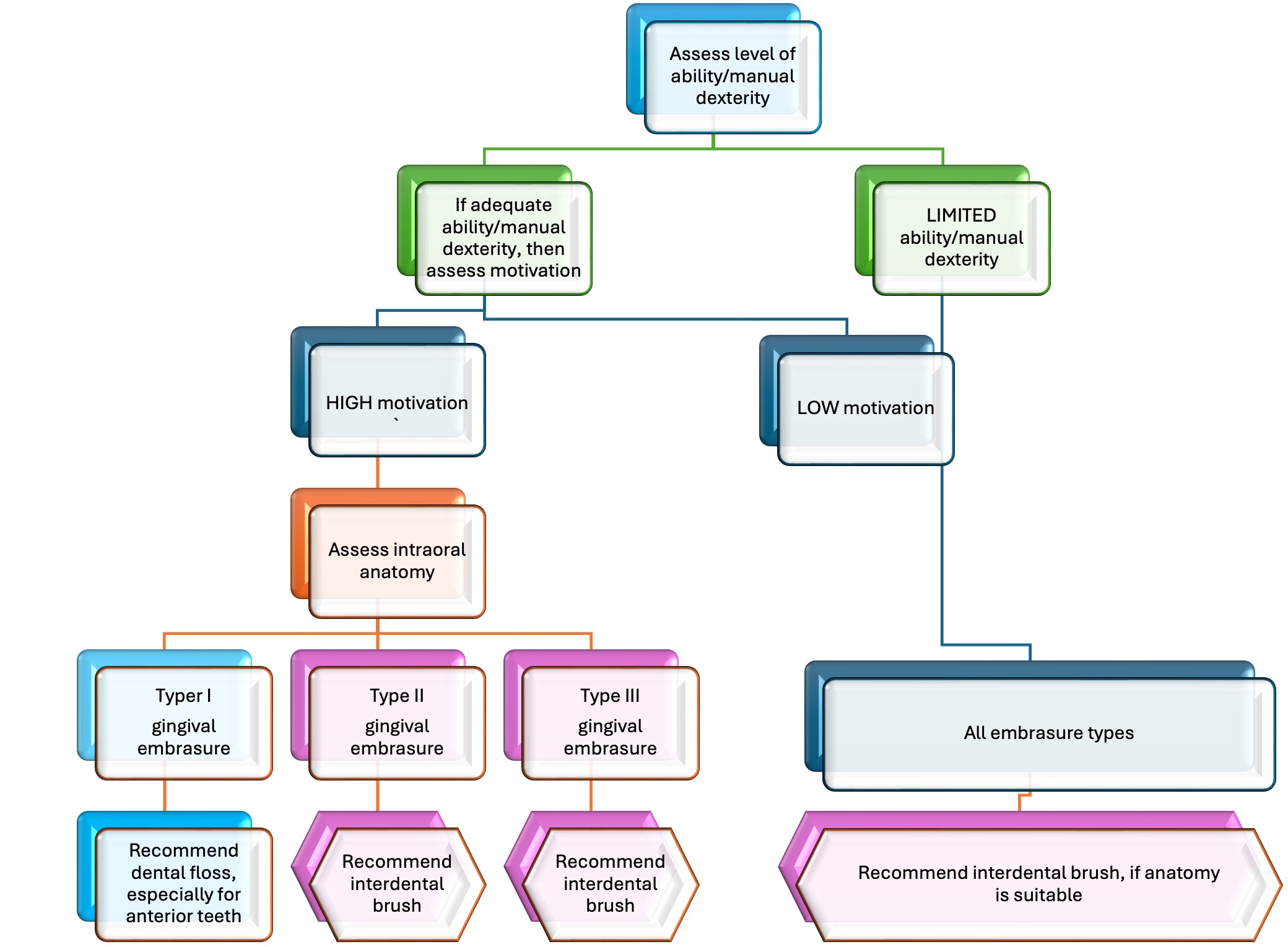

The Canadian Dental Hygiene Association (CDHA) offers a decision-making tree (available at www.cdha.ca) to simplify the selection process for interdental hygiene devices. This pragmatic flowchart helps tailor device recommendations based on patient-specific conditions, ensuring optimal biofilm management in interdental spaces.

When is dental floss the right choice?

Selecting the most suitable device for interdental hygiene involves assessing the patient’s manual dexterity, motivation, and the anatomy of their interdental spaces. Dental floss is generally appropriate for patients with healthy teeth and gums and narrow interdental spaces, as it can effectively remove biofilm in such cases. However, it is crucial to also evaluate posterior interdental spaces, as interdental brushes, when accessible, are often more effective and better accepted by patients.

For gingival embrasures classified as Type II or III, interdental brushes should be the first choice due to their superior cleaning capability in these wider spaces.

Mastering the use of dental floss

Once dental floss is chosen for cleaning interdental spaces, it is essential to train the patient in the proper flossing technique.

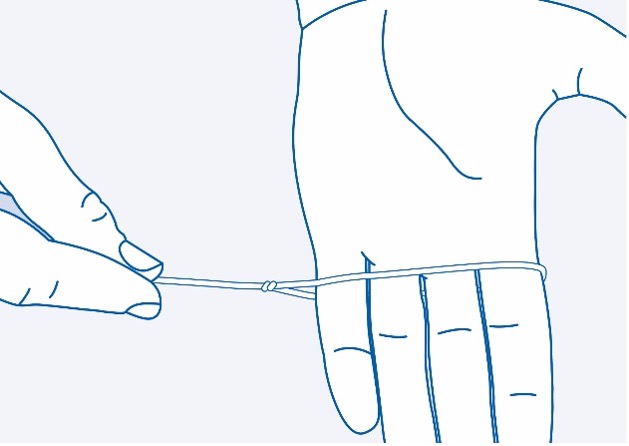

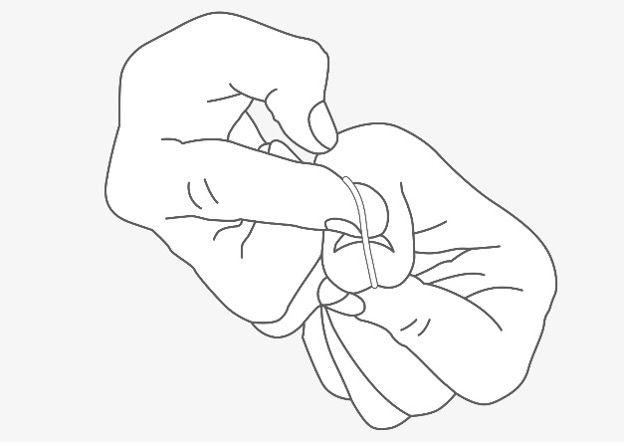

There are two common methods for holding dental floss:

- Traditional Technique: Wrapping the floss around the fingers.

- Loop Technique: Creating a loop with the floss, which can simplify handling and improve control during flossing.

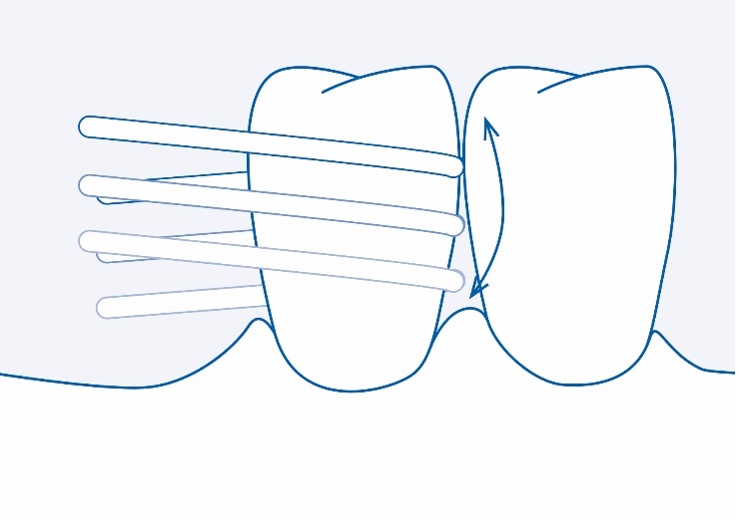

When flossing, it is important to use a short segment of floss, carefully wrapping it around the tooth’s crown to create a “C-shape” before gently sliding it into the subgingival space. This ensures effective biofilm removal while minimising the risk of trauma.

What to do if interdental brushes are selected?

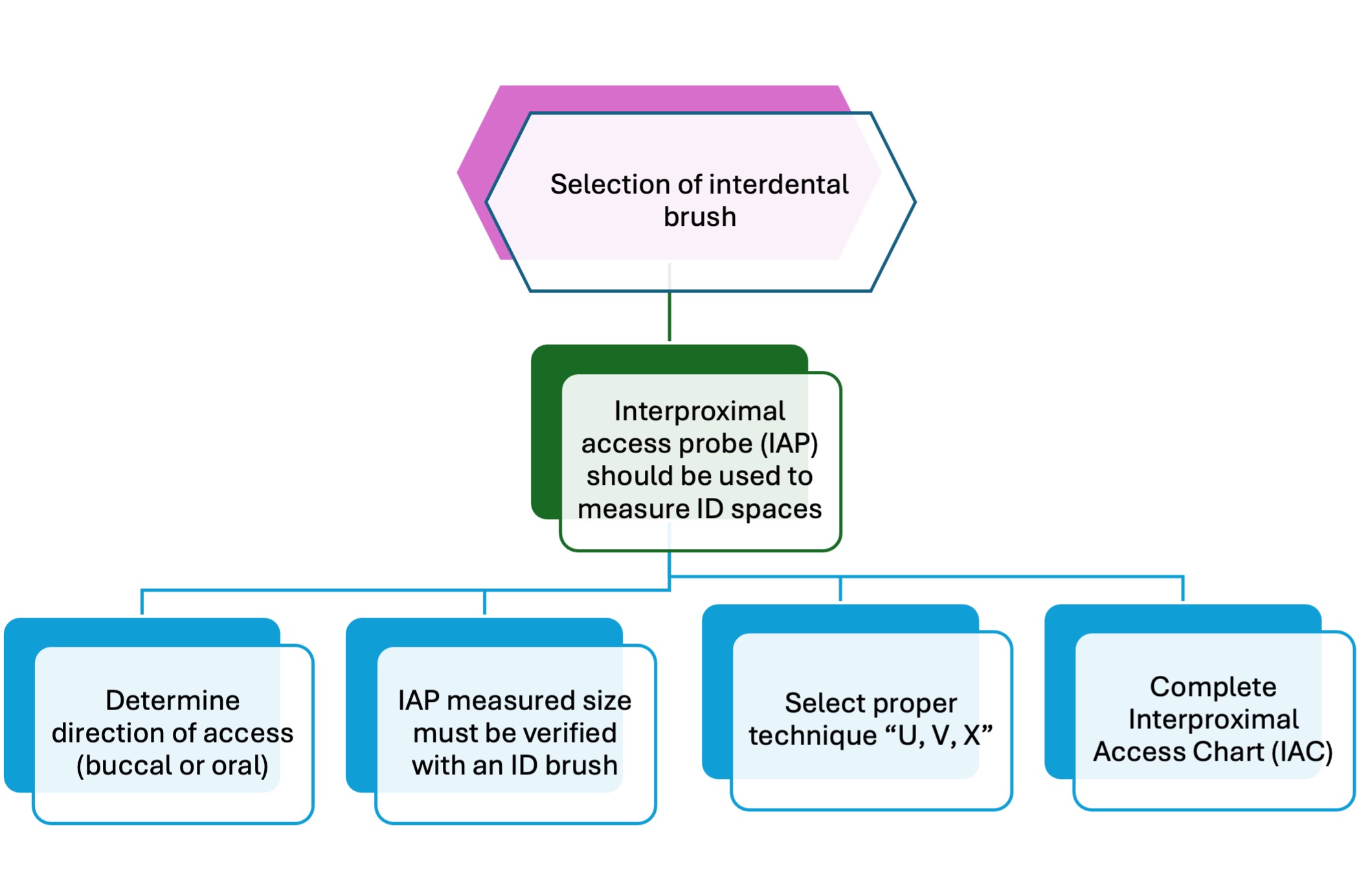

Evidence from studies shows that most interdental spaces, even in young adults with healthy periodontal tissues, especially in the premolar and molar regions, can accommodate smaller-sized interdental brushes. To achieve optimum effectiveness and minimize trauma to the interdental papilla, several important steps should be incorporated into clinical practice to assist with the selection of interdental brushes and reduce guesswork.

Why does the size of the interdental brush matter?

The brush size must fit snugly within the interdental space to ensure effective biofilm removal without the wire core coming into contact with the proximal surfaces of adjacent teeth.

Direction of insertion

Studies and clinical experience suggest that interdental brushes should ideally be inserted in a buccal-to-oral direction to ensure easier access and optimal cleaning efficacy. However, in certain cases, particularly around the upper and lower second molars, lingual access may be more practical and convenient for the patient.

How to gently insert an interdental brush into a narrow interdental space?

For gingival types II and III embrasures, a one-step approach can be used, as the interdental space is visible and easily accessible. However, when the interdental space is narrow and filled with papilla, a “three-step” or” U” shape approach may be necessary to prevent trauma.

Interproximal Access Chart (IAC)

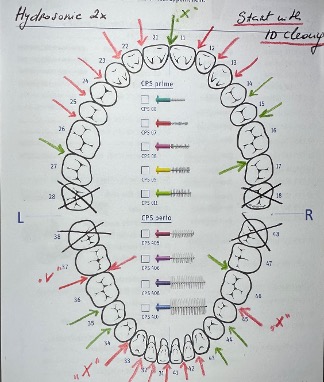

After measuring and determining the appropriate size of interdental brushes and the brushing technique, the clinician should complete the Interproximal Access Chart (IAC) for the patient to use at home while cleaning their interdental spaces.

In this process, the most important factor is selecting interdental brushes of the proper size according to the current anatomy and the patient’s needs. Two common mistakes related to interdental (ID) hygiene recommendations made by dental professionals are:

• Recommending too many sizes at once (more than two to three sizes)

• Not considering the dynamics of ID spaces

Patients are more likely to become confused if they are given a complex task to manage, which can negatively impact their compliance. Moreover, if they are not properly monitored, it is likely that their biofilm control technique will deteriorate over time, or the recommended devices and techniques for biofilm control will no longer be effective.

For example, in patients undergoing a course of active periodontal therapy, as inflammation and swelling reduce, the interdental gingiva may recede, exposing ID spaces (black triangles). As a result, the smaller-sized interdental brushes initially recommended may no longer be effective. In such cases, the interdental spaces should be reassessed and re-measured with an Interproximal Access Probe (IAP) to ensure proper biofilm control and prevent disease recurrence.

Therefore, regular reinforcement and T2T session recall, along with a revision of personal oral hygiene needs following iTOP criteria, are of paramount importance for both primary and secondary prevention.

References:

CDHA interdental brushing steatement.pdf

Bourgeois, D., Carrouel, F., Llodra, J. C., Bravo, M. & Viennot, S. A Colorimetric Interdental Probe as a Standard Method to Evaluate Interdental Efficiency of Interdental Brush. Open Dent J.9, 431–7 (2015).

Bourgeois, D., Bravo, M., Llodra, JC. et al.Calibrated interdental brushing for the prevention of periodontal pathogens infection in young adults – a randomized controlled clinical trial. Sci Rep 9, 15127 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51938-8.

Rosenauer T, Wagenschwanz C, Kuhn M, Kensche A, Stiehl S, Hannig C. The Bleeding on Brushing Index: a novel index in preventive dentistry. Int Dent J. 2017 Oct;67(5):299-307. doi: 10.1111/idj.12300. Epub 2017 May 15. PMID: 28503739; PMCID: PMC9378889.

Sälzer S, Slot DE, Van der Weijden FA, Dörfer CE. Efficacy of inter-dental mechanical plaque control in managing gingivitis–a meta-review. J Clin Periodontol. 2015 Apr;42 Suppl 16:S92-105. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12363. PMID: 25581718. Efficacy of inter‐dental mechanical plaque control inmanaging gingivitis – a meta‐review – Sälzer – 2015 – Journal of Clinical Periodontology – Wiley Online Library

The instructional videos and illustrations of the mechanical plaque control devices featured in this section are generously provided by Curaprox to enhance your learning experience.